Raise Money-Smart Kids: The Opposite of Spoiled, by Ron Lieber

I can’t claim to be an expert on raising children. In fact, this is one of many, many topics about which I am not an expert. I do not have children of my own, and my observations of my friends and their children are limited. My experience comes from my memory as a child being raised by my parents.

To be honest, I have no idea how my parents managed my development into a somewhat capable adult or what they were thinking at the time, even though I do have a younger brother and had the chance to do a little more observation.

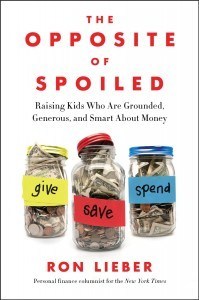

Ron Lieber’s new book, The Opposite of Spoiled: Raising Kids Who Are Grounded, Generous, and Smart About Money (Harper, on sale February 3, 2015) will serve as the perfect how-to guide for when I do have children of my own. I will want my offspring to have a well-developed sense of self, including financial issues, long before I did. Maybe I can prevent repetition of some of the mistakes that I lived through, all though sometimes mistakes offer the best opportunities for learning.

Lieber uses his book as an opportunity to encourage parents to start discussions with their children and to guide them in those discussions. In many cases, there are no absolute answers or rules that work for every parent, every child, in every situation. That would be an impossible task, as the financial realities of families wildly, as do children’s developmental processes.

This variety is skillfully woven throughout the book to give readers enough examples and counterexamples to spur reflection and consideration among parents who may not have given money discussions with children much thought. Many of the examples come from Ron Lieber’s community of readers through his column and blog in The New York Times and on Facebook. The author spent a year meeting with many of the families who contacted him to share their experiences, challenges, and decisions.

One anecdote that stuck with me came in a section in which Lieber shared discussions about children who work. I had jobs when I was a teenager, including one retail, but mostly office jobs. These jobs helped me earn a little bit of money, but didn’t really instill much about responsibility. My jobs came during school breaks for the most part, as I believed, as I think my parents did, that education was my priority, and that my “job” was to do well in school.

The author shared a story about a family of nine in Lewiston, Utah, raising 1,800 cows on the family farm. Unlike my life growing up, the children in this family have no time for extracurricular activities.

There is a presumption that [youngest family member Zeb] will work, that his family members will teach him how, and that he will be good at it, quickly. And while none of the boys is a great scholar or a star athlete, their parents operate under the assumption that the ability to perform basic labor is something within every child’s grasp. They know that every boy will grow up to work in the family business, but they’re confident that none of them will be afraid of the effort it takes to succeed someplace else.

The idea of this hard work leads to a discussion elsewhere in the book about the quality of “grit.” Measurements of grit, or how well someone persists, particularly through obstacles, correlates more tightly with direct measures of success than other types of aptitude, like IQ. Allowing children to develop grit through work gives them the ability to handle much more of life as an adult.

An important section of The Opposite of Spoiled focuses on instilling gratitude. Spoiled children show no gratitude for the advantages they have. Lieber offers specific suggestions for dealing with the observations kids have even at an unexpectedly young age. How do you explain socio-economic status to kids who are aware of being rich or being poor through their own observations?

The author points to this research:

[A researcher…] showed 3-year-olds a series of photographs and distinguished between the haves and have-nots. Only half of her subjects thought that the rich and poor people would be friends with each other. Other research has shown that 6-year-olds keep score of which kids have what sorts of possessions and begin to make judgments accordingly. By 11 or so, they’re beginning to assume that social class is related to ambition. Around age 14, they begin to wonder if there is a larger economic system at work that may constrain movement between classes.

It’s safe to say we all know some adults whose attitudes may be stuck at the development level between the ages of 11 and 14. But the book offers great suggestions for addressing issues of class without instilling pity or jealousy.

Lieber also addresses some of the more controversial aspects of child development pertaining to money, allowance and charitable giving.

I don’t read many personal finance books. After a decade of reading some of the best and some of the most laughable, I’ve been kind of burned out by the genre. For the last year, I’ve been selecting my reading carefully. I was initially excited about the opportunity to read Lieber’s latest because I am a fan of his columns in The New York Times, and his articles have often served as inspiration for the topics I’ve covered on Consumerism Commentary.

I’m glad that The Opposite of Spoiled didn’t disappoint. While many readers of Consumerism Commentary have shared their own stories over the years, the concise collection of advice found within The Opposite of Spoiled has offered me new perspectives for raising my future children to be empathetic, understanding, generous, and smart.

Pre-order The Opposite of Spoiled: Raising Kids Who Are Grounded, Generous, and Smart About Money by Ron Lieber now, in hardcover or Kindle edition.

Raise Money-Smart Kids: The Opposite of Spoiled, by Ron Lieber is a post from Consumerism Commentary. New to Consumerism Commentary? Start here.

![]()

SOURCE: Consumerism Commentary – Read entire story here.